Understanding social-emotional functioning

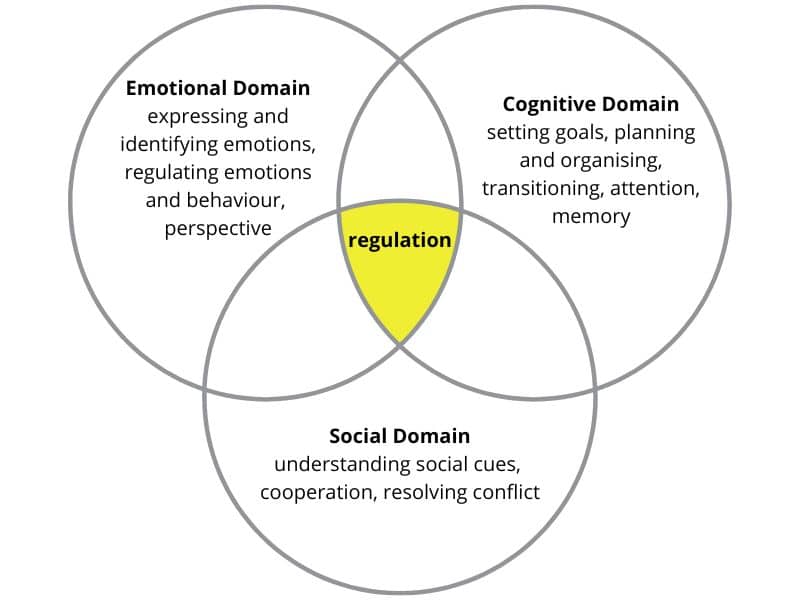

Social-emotional functioning refers to a broad set of interconnected and interdependent competencies that determine the extent to which children are able to manage their interpersonal relations and learning.1,2

The attributes of social-emotional functioning in the preschool child that have been found to be most closely associated with learning outcomes both during preschool and in later phases of education are: anxiety, aggressive disruptive behaviors, self-control, task persistence (mastery motivation), and social competence (cooperative, socially responsible, and helpful behaviours).3

All children will display signs of anxiety and disruptive behaviour under some circumstances and it is the latter which understandably commands most attention from the teacher. It is when these characteristics are stable and frequently displayed features of behaviour, that further investigation to establish the causes may be indicated. In serious cases that cannot be managed in the classroom, specialist advice may be indicated.

It is not surprising that anxious and withdrawn children are less noticed than those who are aggressive and disruptive. These children may display anxiety and shyness in new situations and prefer solo play to group activities. It is important that teachers recognise these children and engage in sensitive supportive interactions to draw them out and help build confidence.

Some children may be more aggressive, disruptive and disobedient than others. This aspect of emotional functioning impacts their social competence, and also interferes with learning and social relationships (e.g. it can result in unpopularity and exclusion from peer activities). Appropriate classroom management can go a long way in dealing with disruptive children. This includes ensuring children are familiar with the rules and norms of acceptable behaviour, and dealing with violations in a sensitive, firm and consistent manner. Key features of the teacher’s intervention should include calmly explaining how the transgression violates the norms, and most importantly – how it impacts negatively on the other children or the teacher. This aids in the development of perspective taking and understanding the effect of the behaviour on others. Showing children how cooperative behaviour can resolve the situation and praising them when they do is also key because one cannot assume that the children would have these skills (more info).

The link between self-control and academic ability

Self-control is the ability to regulate emotions, thoughts and behaviour. Self-control is a key competence required to benefit from the learning environment and is a component of Cognitive Executive Functioning – one of the 5 developmental domains which are assessed with ELOM. Children with age-appropriate self-control are able to manage their emotions in interactions with peers and teachers and focus on the task at hand, so that learning is not disrupted by distress, poor attention and frustration. Children with good self-control are able to deal with the challenges of material they find difficult, and cope with failure without significant distress. While they might be disappointed at not managing a task, or not being chosen to play with peers, this will not likely be accompanied by an emotional outburst, prolonged unhappiness or withdrawal. Children who display self-control are more likely to work persistently on tasks and listen to the teachers’ instructions. A child’s task persistence (spending time in mastering a problem) is another important influence on learning outcomes in preschool and beyond. Success feeds into and reinforces children’s sense of their own ability, also known as academic self-efficacy. Here is an useful guide on promoting these important skills.

In sum, children’s emotional states influence their ability to engage with the preschool or school environment and benefit from the curriculum. Children who are able to manage their anxiety and regulate their emotions and behaviour and have a positive sense of self and their own abilities, are more able to engage in learning. Their social competence enhances their ability to engage cooperatively and productively with peers and teachers in the learning environment. Both social and emotional functioning therefore come together to influence children’s learning outcomes.

The relationship between social-emotional functioning, other developmental domains and early school achievement

The research evidence indicates that social-emotional functioning, while important in influencing adjustment to school, is associated with performance in all areas of academic performance4 and not with achievement in specific domains unless the subject matter is challenging for them (see the ELOM findings reported below). For example, challenges in learning to read or in performing calculations may cause anxiety concerning those subjects. Children with a low sense of academic self-efficacy do perform worse in these areas.5 It is likely that the relationship is bi-directional (good performance reinforces the child’s sense of academic self-efficacy).

Generalised anxiety is likely to compromise children’s learning and academic achievement in a broad spectrum of learning areas. The same goes for children who display disruptive behaviour for various reasons, including hyperactivity and attention deficit disorders.

Lessons from the ELOM data

The ELOM Teacher Assessment measures social-emotional functioning on two scales: the Social Relations with Peers and Adults Scale, and the Emotional Readiness for School Scale. In the Thrive by Five Index, the two scales were combined, and this composite social-emotional measure predicted ELOM 4&5 Total scores. Domain relationships have not yet been explored.

An evaluation of Smartstart found that both of the ELOM Teacher Assessment scales separately predicted ELOM Total scores and also performance on the Emergent Numeracy and Mathematics domain. In an examination of the effects of playgroup participation on ELOM 4&5 scores, the Social Relations with Peers and Adults Scale (but not the Emotional Readiness for School Scale), predicted ELOM 4&5 Total and all domains except Gross Motor Development.6 These are promising early findings that align with research showing links between social functioning, persistence and aspects of executive functioning with academic skills. More research on the relationship between these two areas on ELOM domains is needed.

This article was written by Andy Dawes, Associate Professor Emeritus in the Department of Psychology at the University of Cape Town.

References

- Collie, R. J., Martin, A. J., Nassar, N., & Roberts, C. L. (2019). Social and emotional behavioral profiles in kindergarten: A population-based latent profile analysis of links to socio-educational characteristics and later achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 111(1), 170-187.

- Campbell, S. B., Denham, S. A., Howarth, G. Z., Jones, S. M., Whittaker, J. V., Williford, A. P., … & Darling-Churchill, K. (2016). Commentary on the review of measures of early childhood social and emotional development: Conceptualization, critique, and recommendations. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 45, 19-41.

- Bornstein, M. H., Hahn, C. S., & Haynes, O. M. (2010). Social competence, externalizing, and internalizing behavioral adjustment from early childhood through early adolescence: Developmental cascades. Development and psychopathology, 22(4), 717-735.

- McClelland, M. M., Morrison, F. J., & Holmes, D. L. (2000). Children at risk for early academic problems: The role of learning-related social skills. Early childhood research quarterly, 15(3), 307-329. Alzahrani, M., Alharbi, M., & Alodwani, A. (2019). The Effect of Social-Emotional Competence on Children Academic Achievement and Behavioral Development. International Education Studies, 12(12), 141-149.

- Liew, J., E. McTigue, et al. (2008). Adaptive and effortful control and academic self-efficacy beliefs on achievement: A longitudinal study of 1st through 3rd graders. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 23, 515-526.

- Dawes, A., Biersteker, L., Snelling, M., Horler, J., & Girdwood, E. (2023). To What Extent Can Community-based Playgroup Programmes Targeting Low-income Children Improve Learning Outcomes Prior to Entering the Reception Year in South Africa? A Quasi-experimental Field Study. Early Education and Development, 34(1), 256-273.